Our spring roster of trips is now ready! Current Hanover Conservancy members will receive a colorful announcement shortly. Come explore with us! Our trips are free and open to all.

Follow the link below for a list of our upcoming trips.

Our spring roster of trips is now ready! Current Hanover Conservancy members will receive a colorful announcement shortly. Come explore with us! Our trips are free and open to all.

Follow the link below for a list of our upcoming trips.

Emerald Borer in Hanover: A discussion this Wednesday at Howe Library with Bill Davidson at NH Division of Forests & Lands.

When: Wednesday, August 10th at 7pm

Where: Murray Room at the Howe Library

Driving directions:

What you should know:

BRIEF HIKING DIRECTIONS

FULL DIRECTIONS

9 minutes from the junction, cross a log bridge built by Hypertherm volunteers. Listen for the music of a small waterfall just below. This stream, like its sisters on the Mayor-Niles Forest, is part of the headwater network for Hewes Brook, which flows down off the NW slope of Moose Mountain in to Lyme, past Crossroads Academy, and on to the Connecticut River. By protecting these headwater streams, keeping them naturally forested and shaded, the Conservancy protects cool and clean water for brook trout while providing security against downstream flooding during the heavy storms that come with climate change.

9 minutes from the junction, cross a log bridge built by Hypertherm volunteers. Listen for the music of a small waterfall just below. This stream, like its sisters on the Mayor-Niles Forest, is part of the headwater network for Hewes Brook, which flows down off the NW slope of Moose Mountain in to Lyme, past Crossroads Academy, and on to the Connecticut River. By protecting these headwater streams, keeping them naturally forested and shaded, the Conservancy protects cool and clean water for brook trout while providing security against downstream flooding during the heavy storms that come with climate change. Once across the log bridge, keep your eyes out for a tiny forest of Lycopodium, or clubmoss. There are at least 3 species here – ground pine, ground cedar, and shining club moss, miniature ancient cousins of the huge forests that once offered shade to dinosaurs.

Once across the log bridge, keep your eyes out for a tiny forest of Lycopodium, or clubmoss. There are at least 3 species here – ground pine, ground cedar, and shining club moss, miniature ancient cousins of the huge forests that once offered shade to dinosaurs. This rock had some help getting here from nearby Holt’s Ledge in Lyme, but the icy conveyor belt melted and disappeared 14,000 years ago. Spend a few moments admiring the growth of rich moss on its downslope side encouraged by moisture rising from the stream below. Topping the huge rock is a toupee of rock polypody, a tiny evergreen fern that seems to like such perches.

This rock had some help getting here from nearby Holt’s Ledge in Lyme, but the icy conveyor belt melted and disappeared 14,000 years ago. Spend a few moments admiring the growth of rich moss on its downslope side encouraged by moisture rising from the stream below. Topping the huge rock is a toupee of rock polypody, a tiny evergreen fern that seems to like such perches. About 15 minutes’ walk from the big maple, the trail turns L twice before arriving at the end of the loop. Pause here to consider a red spruce at R. It was this species of tree that alerted the country to the scourge of acid rain in the 1980s, when scientists from the University of Vermont noticed waves of dying red spruce on the W slopes of Camel’s Hump…the slopes that caught polluted winds blowing in from industrialized parts of Ohio, Michigan, and SW Ontario. Efforts to control air-borne pollution were successful enough that acid rain is largely a thing of the past and the spruces are recovering, but they face a new threat – climate change. Barely tolerant of warm temperatures, red spruce survives on “sky islands” around the summits of the southern Appalachian Mountains, along the Maine coast, and in higher elevation parts of New England such as this. These populations will surely shrink as the climate warms. Their presence here contributes to wildlife habitat value – offering food and shelter for ruffed grouse, snowshoe hare, and small mammals in times of snow, and is among the many reasons the Conservancy was pleased to protect this land.

About 15 minutes’ walk from the big maple, the trail turns L twice before arriving at the end of the loop. Pause here to consider a red spruce at R. It was this species of tree that alerted the country to the scourge of acid rain in the 1980s, when scientists from the University of Vermont noticed waves of dying red spruce on the W slopes of Camel’s Hump…the slopes that caught polluted winds blowing in from industrialized parts of Ohio, Michigan, and SW Ontario. Efforts to control air-borne pollution were successful enough that acid rain is largely a thing of the past and the spruces are recovering, but they face a new threat – climate change. Barely tolerant of warm temperatures, red spruce survives on “sky islands” around the summits of the southern Appalachian Mountains, along the Maine coast, and in higher elevation parts of New England such as this. These populations will surely shrink as the climate warms. Their presence here contributes to wildlife habitat value – offering food and shelter for ruffed grouse, snowshoe hare, and small mammals in times of snow, and is among the many reasons the Conservancy was pleased to protect this land. You’ve just spent an hour roaming an unbroken forest – another key reason the Britton Forest is important. The property is surrounded on three sides by other forested, protected and/or public lands: the Mayor-Niles Forest to the S, the Appalachian Trail corridor owned by the National Park Service to the E along the mountain’s spine, and the Plummer Tract to the N, owned by the Town of Hanover. Keeping all of these higher elevation forests intact means continuous, cooler room for wildlife to roam, especially as the climate warms.

You’ve just spent an hour roaming an unbroken forest – another key reason the Britton Forest is important. The property is surrounded on three sides by other forested, protected and/or public lands: the Mayor-Niles Forest to the S, the Appalachian Trail corridor owned by the National Park Service to the E along the mountain’s spine, and the Plummer Tract to the N, owned by the Town of Hanover. Keeping all of these higher elevation forests intact means continuous, cooler room for wildlife to roam, especially as the climate warms.

miles on East Wheelock Street, up a long hill to the junction of Grasse and Trescott Roads.

miles on East Wheelock Street, up a long hill to the junction of Grasse and Trescott Roads. rs indicate total number of plants in the fenced plots where deer cannot enter to browse, while red bars indicate the number of plants in the unfenced plots. In 2012, before the fencing went up, both plots had nearly the same number of plants. Contrast that to 2015! The largest change is in the number of wildflowers, especially Canada mayflower.

rs indicate total number of plants in the fenced plots where deer cannot enter to browse, while red bars indicate the number of plants in the unfenced plots. In 2012, before the fencing went up, both plots had nearly the same number of plants. Contrast that to 2015! The largest change is in the number of wildflowers, especially Canada mayflower.

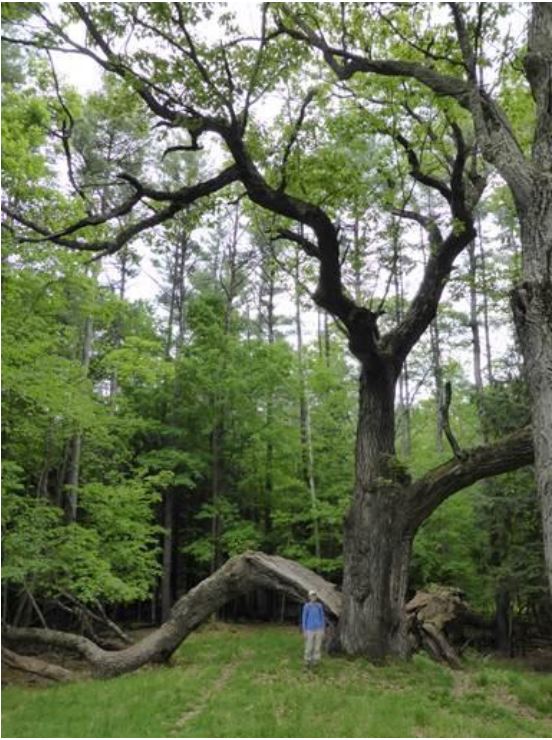

Head back up the Maple and Fire Trails to the summit. Pass the kiosk and nearby bench, and head down to the right toward the Hemlock Trail sign. You’ll soon come to the remains of an enormous old oak tree, its split trunk and massive limbs now draped across the landscape, having lost their battle with gravity and time. The trail actually passes under the fallen trunk. Here’s what it looked like in 2014 (right).

Head back up the Maple and Fire Trails to the summit. Pass the kiosk and nearby bench, and head down to the right toward the Hemlock Trail sign. You’ll soon come to the remains of an enormous old oak tree, its split trunk and massive limbs now draped across the landscape, having lost their battle with gravity and time. The trail actually passes under the fallen trunk. Here’s what it looked like in 2014 (right).The volunteer Balch Hill Stewardship Committee cares for this place and always welcomes help. Contact us if you’d like to get involved! We welcome contributions to the Balch Hill Stewardship Fund to help with the costs of annual mowing, vegetation management, and trail improvements.

place and always welcomes help. Contact us if you’d like to get involved! We welcome contributions to the Balch Hill Stewardship Fund to help with the costs of annual mowing, vegetation management, and trail improvements.

December 2016, updated September 2020

Trees give us many gifts – clean air and water, places to recreate, wildlife habitat…and carbon storage. Restoring trees to the landscape is the single best low-tech, low-cost pathway for storing more carbon on the land. A forest can store an average of 2-3 tons/acre of C02 each year. With just a will and a spade, we can get started pulling carbon from the air right now.

A NATURAL CARBON SINK – To prevent the most dangerous impacts of climate change, greenhouse gas emissions must reach net zero by 2050. Capturing carbon from the air naturally – by putting trees to work – can provide significant cumulative carbon removal through 2050 and beyond.

When choosing a tree for your home landscape, consider this:

We suggest Northern Red Oak — Acorns attract wildlife and the leaves develop a brick-red fall color. Red oak is fast growing, easy to transplant, and tolerant of urban conditions (including dry and acidic soil and air pollution). Best growth is in full sun and well drained, slightly acidic, sandy loam. Northern red oak often reaches 60-90’ and occasionally 150’. Trees may live up to 500 years.

A colorful alternative for damp soils is Red Maple — the most abundant native tree in eastern North America. Known for its early brilliant fall foliage and red flowers, it is usually found in moist woodlands and wet swamps in sun or part shade. A medium-sized, fast-growing tree (2-5’/yr), its seeds and buds are eaten by birds and mammals, but it is not preferred by deer.

Pine Park is Hanover’s first natural area permanently preserved as a park and today functions as the town’s “central park” for the enjoyment of walkers, joggers, skiers and many others. The park is owned by the Pine Park Association, a voluntary nonprofit that dates back to 1900, when a group of 17 local residents sought to prevent the Diamond Match Company from harvesting trees along the riverbank just north of the Ledyard Bridge.

Pine Park is Hanover’s first natural area permanently preserved as a park and today functions as the town’s “central park” for the enjoyment of walkers, joggers, skiers and many others. The park is owned by the Pine Park Association, a voluntary nonprofit that dates back to 1900, when a group of 17 local residents sought to prevent the Diamond Match Company from harvesting trees along the riverbank just north of the Ledyard Bridge.